Northern Lapwing

Case 2, Bird 2: The Northern Lapwing

The Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus), also known as the Peewit, Green Plover or (in the British Isles) just Lapwing, is a bird in the plover family. It is common through temperate Eurasia. It is highly migratory over most of its extensive range, wintering further south as far as north Africa, northern India, Pakistan, and parts of China. It migrates mainly by day, often in large flocks. Lowland breeders in westernmost areas of Europe are resident. It occasionally is a vagrant to North America, especially after storms, as in the Canadian sightings after storms in December 1927 and in January 1966. It is a wader which breeds on cultivated land and other short vegetation habitats. 3–4 eggs are laid in a ground scrape. The nest and young are defended noisily and aggressively against all intruders, up to and including horses and cattle. In winter it forms huge flocks on open land, particularly arable land and mud-flats. The name lapwing has been variously attributed to the “lapping” sound its wings make in flight, from the irregular progress in flight due to its large wings (OED derives this from an Old English word meaning “to totter”), or from its habit of drawing potential predators away from its nest by trailing a wing as if broken. Peewit describes the bird’s shrill call. This is a vocal bird in the breeding season, with constant calling as the crazed tumbling display flight is performed by the male. It feeds primarily on insects and other small invertebrates. This species often feeds in mixed flocks with Golden Plovers and Black-headed Gulls, the latter often robbing the two plovers, but providing a degree of protection against predators. Like the Golden Plovers, this species prefers to feed at night when there are moonlit nights.(Wikipedia)

Regent Bowerbird

The Regent Bowerbird, Sericulus chrysocephalus is a medium-sized, up to 25 cm long, sexually dimorphic bowerbird. The male bird is black with a golden orange-yellow crown, mantle and black-tipped wing feathers. It has yellow bill, black feet and yellow iris. The female is a brown bird with whitish or fawn markings, grey bill, black feet and crown. All male bowerbirds build bowers, which can be simple ground clearings or elaborate structures, to attract female mates. Regent Bowerbirds in particular are known to mix a muddy greyish blue or pea green “saliva paint” in their mouths which they use to decorate their bowers. Regents will sometimes use wads of greenish leaves as “paintbrushes” to help spread the substance, representing one of the few known instances of tools used by birds. An Australian endemic, the Regent Bowerbird is distributed to rainforests and margins of eastern Australia, from central Queensland to New South Wales. The diet consists mainly of fruits, berries and insects. The male builds an avenue-type bower consisting of two walls of sticks, decorated with shells, seeds, leaves and berries. The name commemorates the Prince Regent of the United Kingdom. A common species throughout its range, the Regent Bowerbird is evaluated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.(Wikipedia)

Eastern Bluebird

Case 2, Bird 7: The Eastern Bluebird

The Eastern Bluebird, Sialia sialis, is a small thrush found in open woodlands, farmlands and orchards, and most recently can be spotted in suburban areas. It is the state bird of Missouri and New York. Approximately two-thirds of the diet of an adult eastern bluebird consists of insects and other invertebrates. The remainder of the bird’s diet is made up of wild fruits. Favored insect foods include grasshoppers, crickets, katydids, and beetles. Other food items include earthworms, spiders, millipedes, centipedes, sow bugs and snails. Fruits are especially important when insects are scarce in the winter months. Some preferred winter food sources include dogwood, hawthorn, wild grape, and sumac and hackberry seeds. Supplemental fruits eaten include blackberries, bayberries, fruit of honeysuckle, Virginia creeper, Eastern Juniper and pokeberries. Bluebirds feed by perching on a high point, such as a branch or fence post, and swooping down to catch insects on or near the ground. The availability of a winter food source will often determine whether or not a bird will migrate. If bluebirds do remain in a region for the winter, they will group and seek cover in heavy thickets, orchards, or other areas in which adequate food and cover resources are available. If you want to attract these species, put crunched-up peanuts in a feeder about four feet off the ground. Eastern bluebirds prefer to nest in woodlands where cavity holes excavated by a previous species will serve as their home. These woodlands must be near clearings or meadows because this is the preferred hunting ground of the species. River or creek access is an added benefit and preferred. Keep these things in mind when placing a nestbox on your property. Determined bluebird lovers may wish to pay attention to nestbox size (overly large boxes can invite deadly raids by non-native Common Starlings). The entrance hole should be 1 1/2″ diameter for Eastern Bluebirds, and the box should have good ventilation. Active and/or passive pest control is also greatly useful against non-native House Sparrows — these are small enough to enter bluebird boxes and kill bluebirds, destroy nests. Although doing well now, Eastern Bluebird populations declined to a level raising extinction fears by the 1960s, and in large part, the volunteer intervention of bluebird lovers in Eastern North America brought the species back by implementing the above. Such practices and the organizations promoting them remain important for stable populations today. An activist writes, “The most significant factor in the recent population recovery is volunteerism – by young and old – people like you – doing their part by putting up and monitoring nestboxes, spreading the word, and encouraging others to get involved.” (Wikipedia)

Northern Bobwhite Quail

Case 2, Bird 8: Northern Bobwhite Quail

Northern Bobwhite, Virginia Quail or (in its home range) Bobwhite Quail (Colinus virginianus) is a ground-dwelling bird native to the United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean. It is a member of the group of species known as New World quails (Odontophoridae). They were initially placed with the Old World quails in the pheasant family (Phasianidae), but are not particularly closely related. The name “bobwhite” derives from its characteristic whistling call. Despite its secretive nature, the northern bobwhite is one of the most familiar quails in eastern North America because it is frequently the only quail in its range. There are 22 subspecies of Northern Bobwhite, and many of the birds are hunted extensively as game birds. One subspecies, the Masked Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus ridgewayi), is listed as endangered with wild populations located in Sonora, Mexico and a reintroduced population in Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge in Southern Arizona. The Northern Bobwhite’s diet consists of arthropod prey as well as lush vegetation. Northern bobwhites can be found year-round in agricultural fields, grassland, open woodland areas, roadsides and wood edges. Their range covers the southeastern quadrant of the United States from the Great Lakes and southern Minnesota east to Pennsylvania and southern Massachusetts, and extending west to southern Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and all but westernmost Texas. These birds are absent from the southern tip of Florida and the highest elevations of the Appalachian Mountains, but are found in eastern Mexico and in Cuba. Isolated populations of these game birds have been introduced in Oregon and Washington. The Bobwhite has also been introduced to New Zealand. The clear whistle “bob-WHITE” or “bob-bob-WHITE” call of these birds is most recognizable. The syllables are slow and widely spaced, rising in pitch a full octave from beginning to end. Other calls include lisps, peeps and more rapidly whistled warning calls. Like most game birds, the northern bobwhite is shy and elusive. When threatened, it will crouch and freeze, relying on camouflage to stay undetected, but will flush into low flight if closely disturbed. These birds are generally solitary or found in pairs early in the year, but family groups are common in the late summer and winter roosts may have two dozen or more birds in a single covey. These are generally monogamous birds, though some evidence of polygamy has been noted. Both parents will incubate a brood for 23–24 days, and the precocial young leave the nest shortly after hatching. Both parents will lead the young birds to food and care for them for 14–16 days until their first flight. These birds can raise 1-2 broods of 12-16 eggs per brood annually. Game birds are not typical backyard birds, but in the appropriate habitat these birds will visit ground feeders for seeds or cracked corn. They will also visit ground-level bird baths. Birders who want to encourage northern bobwhites to visit should avoid insecticide sprays and choose low shrubs for landscaping to help the birds feel secure.(Wikipedia)

Crimson Rosella

Case 2, Bird 9: Crimson Rosella

The Crimson Rosella (Platycercus elegans) is a parrot native to eastern and south eastern Australia which has been introduced to New Zealand and Norfolk Island. It is commonly found in, but not restricted to, mountain forests and gardens. The Crimson Rosella occurs from southeastern South Australia, through Tasmania, Victoria and coastal New South Wales into Southeastern Queensland. A disparate population occurs in North Queensland.

It is common in coastal and mountain forests at all altitudes. It primarily lives in forests and woodlands, preferring older and wetter forests. They can be found in tropical, subtropical, and temperate rainforests, both wet and dry sclerophyllous forests, riparian forests, and woodlands, all the way from sea-level up to the tree-line. They will also live in human-affected areas such as farmlands, pastures, fire-breaks, parks, reserves, gardens, and golf-courses. They are rarely found in treeless areas. At night, they roost on high tree branches.

Almost all Rosellas are sedentary, although occasional populations are considered nomadic; no Rosellas are migratory. Outside of the breeding season, Crimson Rosellas tend to congregate in pairs or small groups and feeding parties. The largest groups are usually composed of juveniles, who will gather in flocks of up to 20 individuals. When they forage, they are conspicuous and chatter noisily. Rosellas are monogamous, and during the breeding season, adult birds will not congregate in groups and will only forage with their mate.

Crimson Rosellas forage in trees, bushes, and on the ground for the fruit, seeds, nectar, berries, and nuts of a wide variety of plants, including members of the Myrtaceae, Asteraceae, and Rosaceae families. Despite feeding on fruits and seeds, Rosellas are not useful to the plants as seed-spreaders, because they crush and destroy the seeds in the process of eating them. Their diet often puts them at odds with farmers whose fruit and grain harvests can be damaged by the birds, which has resulted in large numbers of Rosellas being shot in the past. Rosellas will also eat many insects and their larvae, including termites, aphids, beetles, weevils, caterpillars, moths, and water boatmen.

Nesting sites are hollows greater than 1 meter (3 feet) deep in tree trunks, limbs, and stumps. These may be up to 30 meters (100 feet) above the ground. The nesting site is selected by the female. Once the site is selected, the pair will prepare it by lining it with wood debris made from the hollow itself by gnawing and shredding it with their beaks. They do not bring in material from outside the hollow. Only one pair will nest in a particular tree. A pair will guard their nest by perching near it at chattering at other Rosellas that approach. They will also guard a buffer zone of several trees radius around their nest, preventing other pairs from nesting in that area.

The breeding season of the Crimson Rosella lasts from September through to February, and varies depending on the rainfall of each year; it starts earlier and lasts longer during wet years. The laying period is on average during mid- to late October. Clutch size ranges from 3-8 eggs, which are laid asynchronously at an average interval of 2.1 days; the eggs are white and slightly shiny and measure 28 x 23 mm. The mean incubation period is 19.7 days, and ranges from 16–28 days. Only the mother incubates the eggs. The eggs hatch around mid December; on average 3.6 eggs successfully hatch. There is a bias towards female nestlings, as 41.8% of young are male. For the first six days, only the mother feeds the nestlings. After this time, both parents feed them. The young become independent in February, after which they spend a few more weeks with their parents before departing to become part of a flock of juveniles. Juveniles reach maturity (gain adult plumage) at 16 months of age.

Crimson Rosellas may be eaten by cats or dogs, and have been found to make up a small part of the diet of the fox in some areas. Possums and currawongs are also believed to occasionally take eggs from the nest. Surprisingly, however, the Crimson Rosella is its own worst enemy. During the breeding season, it is common for females to fly to other nests and destroy the eggs and in fact, this is the most common cause for an egg failing to hatch. This behavior is thought to be a function of competition for suitable nesting hollows, since a nest will be abandoned if all the eggs in it are destroyed, and a pair of Rosellas will tend to nest in the same area from year to year.(Wikipedia)

It is common in coastal and mountain forests at all altitudes. It primarily lives in forests and woodlands, preferring older and wetter forests. They can be found in tropical, subtropical, and temperate rainforests, both wet and dry sclerophyllous forests, riparian forests, and woodlands, all the way from sea-level up to the tree-line. They will also live in human-affected areas such as farmlands, pastures, fire-breaks, parks, reserves, gardens, and golf-courses. They are rarely found in treeless areas. At night, they roost on high tree branches.

Almost all Rosellas are sedentary, although occasional populations are considered nomadic; no Rosellas are migratory. Outside of the breeding season, Crimson Rosellas tend to congregate in pairs or small groups and feeding parties. The largest groups are usually composed of juveniles, who will gather in flocks of up to 20 individuals. When they forage, they are conspicuous and chatter noisily. Rosellas are monogamous, and during the breeding season, adult birds will not congregate in groups and will only forage with their mate.

Crimson Rosellas forage in trees, bushes, and on the ground for the fruit, seeds, nectar, berries, and nuts of a wide variety of plants, including members of the Myrtaceae, Asteraceae, and Rosaceae families. Despite feeding on fruits and seeds, Rosellas are not useful to the plants as seed-spreaders, because they crush and destroy the seeds in the process of eating them. Their diet often puts them at odds with farmers whose fruit and grain harvests can be damaged by the birds, which has resulted in large numbers of Rosellas being shot in the past. Rosellas will also eat many insects and their larvae, including termites, aphids, beetles, weevils, caterpillars, moths, and water boatmen.

Nesting sites are hollows greater than 1 meter (3 feet) deep in tree trunks, limbs, and stumps. These may be up to 30 meters (100 feet) above the ground. The nesting site is selected by the female. Once the site is selected, the pair will prepare it by lining it with wood debris made from the hollow itself by gnawing and shredding it with their beaks. They do not bring in material from outside the hollow. Only one pair will nest in a particular tree. A pair will guard their nest by perching near it at chattering at other Rosellas that approach. They will also guard a buffer zone of several trees radius around their nest, preventing other pairs from nesting in that area.

The breeding season of the Crimson Rosella lasts from September through to February, and varies depending on the rainfall of each year; it starts earlier and lasts longer during wet years. The laying period is on average during mid- to late October. Clutch size ranges from 3-8 eggs, which are laid asynchronously at an average interval of 2.1 days; the eggs are white and slightly shiny and measure 28 x 23 mm. The mean incubation period is 19.7 days, and ranges from 16–28 days. Only the mother incubates the eggs. The eggs hatch around mid December; on average 3.6 eggs successfully hatch. There is a bias towards female nestlings, as 41.8% of young are male. For the first six days, only the mother feeds the nestlings. After this time, both parents feed them. The young become independent in February, after which they spend a few more weeks with their parents before departing to become part of a flock of juveniles. Juveniles reach maturity (gain adult plumage) at 16 months of age.

Crimson Rosellas may be eaten by cats or dogs, and have been found to make up a small part of the diet of the fox in some areas. Possums and currawongs are also believed to occasionally take eggs from the nest. Surprisingly, however, the Crimson Rosella is its own worst enemy. During the breeding season, it is common for females to fly to other nests and destroy the eggs and in fact, this is the most common cause for an egg failing to hatch. This behavior is thought to be a function of competition for suitable nesting hollows, since a nest will be abandoned if all the eggs in it are destroyed, and a pair of Rosellas will tend to nest in the same area from year to year.(Wikipedia)

Great Gray Shrike

Case 2, Bird 10: The Great Grey Shrike

The Great Grey Shrike, Northern Grey Shrike, or Northern Shrike (Lanius excubitor) is a large songbird species in the shrike family (Laniidae). Breeding takes place generally north of 50° northern latitude in northern Europe and Asia, and in North America (where it known as the Northern Shrike) north of 55° northern latitude in Canada and Alaska. Most populations migrate south in winter to temperate regions.The Great Grey Shrike is carnivorous, with rodents making up over half its diet.

The Great Grey Shrike occurs throughout most temperate and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The preferred habitat is generally open grassland, perhaps with shrubs interspersed, and adjacent lookout points. These are normally trees – at forest edges in much of the habitat, but single trees or small stands at the taiga-tundra border. Apart from grassland, the birds will utilize a variety of hunting habitats, including bogs, clearings or non-industrially farmed fields. Breeding birds appear to have different microhabitat desires, but little detail is known yet.

This species is territorial, but likes to breed in dispersed groups of a good half-dozen adults. Throughout the breeding season, in prime habitat territories are held by mated pairs and single males looking for a partner. On the wintering grounds, pairs separate to account for the lower amount of food available at that time, but if both members migrate they tend to have their wintering grounds not far apart. As it seems, once an individual Great Grey Shrike has found a wintering territory it likes, it will return there subsequently and perhaps even try to defend it against competitors just like a summer territory.

The flight of the Great Grey Shrike is undulating and rather heavy, but its dash is straight and determined. It is also capable of hoverflights, which last briefly but may be repeated time after time because of the birds’ considerable stamina. It will usually stay low above the ground in flight, approaching perches from below and landing in an upward swoop. reproduction.

The Great Grey Shrike eats small vertebrates and large invertebrates. To hunt, this bird perches on the topmost branch of a tree, telegraph pole or similar elevated spot in a characteristic upright stance some meters/yards (at least one and up to 18 m/20 yd) above ground. Alternatively, it may scan the grassland below from flight, essentially staying in one place during prolonged bouts of mainly hovering flight that may last up to 20 minutes. The keen eye of the watchful “sentinel” misses nothing that moves. It will drop down in a light glide for terrestrial prey or swoop hawk-like on a flying insect. Small birds are sometimes caught in flight too, usually by approaching them from below and behind and seizing their feet with the beak. If no prey ventures out in the open, Great Grey Shrikes will rummage through the undergrowth or sit near to hiding places and flash their white wing and tail markings to scare small animals into coming out. As noted above, it will sometimes mimic songbirds to entice them to come within striking distance.

Typically, at least half the prey biomass is made up from small rodents such as mice, shrews, lizards, frogs and toads. Prey is killed by hitting it with the hooked beak, aiming for the skull in vertebrates. If too large to swallow in one or a few chunks, it is transported to a feeding site by carrying it in the beak or (if too large) in the feet. The feet are not suited for tearing up prey, however. It is rather impaled upon a sharp point – thorns or the barbs of barbed wire – or wedged firmly between forking branches. Thus secured, the food can be ripped into bite-sized pieces with the beak.

Great Grey Shrikes breed during the summer, typically once per year. In exceptionally good conditions, they raise two broods a year, and if the first clutch is destroyed before hatching they are usually able to produce a second one. Females may deposit their eggs in neighbors’ nests, but this seems to occur more rarely; in general, mated females are fairly reclusive after their eggs have started developing. A full clutch of eggs can be produced by a female in about 10–15 days. Laying usually takes place in May. The clutch numbers 3–9 eggs, typically around 7, with North American clutches tending to be larger on average than European ones. If a second clutch is produced in one breeding season, it is smaller than the first one.(Wikipedia)

The Great Grey Shrike occurs throughout most temperate and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The preferred habitat is generally open grassland, perhaps with shrubs interspersed, and adjacent lookout points. These are normally trees – at forest edges in much of the habitat, but single trees or small stands at the taiga-tundra border. Apart from grassland, the birds will utilize a variety of hunting habitats, including bogs, clearings or non-industrially farmed fields. Breeding birds appear to have different microhabitat desires, but little detail is known yet.

This species is territorial, but likes to breed in dispersed groups of a good half-dozen adults. Throughout the breeding season, in prime habitat territories are held by mated pairs and single males looking for a partner. On the wintering grounds, pairs separate to account for the lower amount of food available at that time, but if both members migrate they tend to have their wintering grounds not far apart. As it seems, once an individual Great Grey Shrike has found a wintering territory it likes, it will return there subsequently and perhaps even try to defend it against competitors just like a summer territory.

The flight of the Great Grey Shrike is undulating and rather heavy, but its dash is straight and determined. It is also capable of hoverflights, which last briefly but may be repeated time after time because of the birds’ considerable stamina. It will usually stay low above the ground in flight, approaching perches from below and landing in an upward swoop. reproduction.

The Great Grey Shrike eats small vertebrates and large invertebrates. To hunt, this bird perches on the topmost branch of a tree, telegraph pole or similar elevated spot in a characteristic upright stance some meters/yards (at least one and up to 18 m/20 yd) above ground. Alternatively, it may scan the grassland below from flight, essentially staying in one place during prolonged bouts of mainly hovering flight that may last up to 20 minutes. The keen eye of the watchful “sentinel” misses nothing that moves. It will drop down in a light glide for terrestrial prey or swoop hawk-like on a flying insect. Small birds are sometimes caught in flight too, usually by approaching them from below and behind and seizing their feet with the beak. If no prey ventures out in the open, Great Grey Shrikes will rummage through the undergrowth or sit near to hiding places and flash their white wing and tail markings to scare small animals into coming out. As noted above, it will sometimes mimic songbirds to entice them to come within striking distance.

Typically, at least half the prey biomass is made up from small rodents such as mice, shrews, lizards, frogs and toads. Prey is killed by hitting it with the hooked beak, aiming for the skull in vertebrates. If too large to swallow in one or a few chunks, it is transported to a feeding site by carrying it in the beak or (if too large) in the feet. The feet are not suited for tearing up prey, however. It is rather impaled upon a sharp point – thorns or the barbs of barbed wire – or wedged firmly between forking branches. Thus secured, the food can be ripped into bite-sized pieces with the beak.

Great Grey Shrikes breed during the summer, typically once per year. In exceptionally good conditions, they raise two broods a year, and if the first clutch is destroyed before hatching they are usually able to produce a second one. Females may deposit their eggs in neighbors’ nests, but this seems to occur more rarely; in general, mated females are fairly reclusive after their eggs have started developing. A full clutch of eggs can be produced by a female in about 10–15 days. Laying usually takes place in May. The clutch numbers 3–9 eggs, typically around 7, with North American clutches tending to be larger on average than European ones. If a second clutch is produced in one breeding season, it is smaller than the first one.(Wikipedia)

Pine Grosbeak

Case 2, Bird 12: The Pine Grosbeak

The Pine Grosbeak (Pinicola enucleator) is a large member of the true finch family, Fringillidae. It is found in coniferous woods across Alaska, the western mountains of the United States, Canada, and in subarctic Fennoscandia and Siberia. During winter, Pine Grosbeaks in parts of North America move southward, bringing them as far south as the upper Midwest and New England in the United States, but sometimes even further south, especially during an irruption. This species is a very rare vagrant to temperate Europe; in all of Germany for example, not more than 4 individuals and often none at all have been recorded each year since 1980.

Adults have a long forked black tail, black wings with white wing bars and a large bill. Adult males have a rose-red head, back and rump. Adult females are olive-yellow on the head and rump and grey on the back and underparts. Young birds have a less contrasting plumage overall, appearing shaggy when they moult their colored head plumage.

Its voice is geographically variable, and includes a whistled pui pui pui or chii-vli. The song is a short musical warble.

The breeding habitat of the Pine Grosbeak is coniferous forests. They nest on a horizontal branch or in a fork of a conifer. This bird is a permanent resident through most of its range; in the extreme north or when food sources are scarce, they may migrate further south.

The Pine Grosbeak forages in trees and bushes. It mainly eats seeds, buds, berries and insects. Outside of the nesting season, it often feeds in flocks.

The Pine Grosbeak, together with its Himalayan relative the Crimson-browed Finch (P. subhimachala), represents an ancient divergence from the same stock that also gave rise to the true bullfinches (Pyrrhula). The Pinicola lineage diverged from its relatives perhaps a dozen million years ago, during the Clarendonian faunal stage of the mid-Miocene.

At the same time, the evolutionary radiation of Pyrrhula throughout Eurasia and the Holarctic expansion of the closely related Leucosticte mountain finches and relatives began. These genera evolved in the interior of Asia, and thus the original Pinicola stock was probably already a conifer forest bird living to the north of the Himalayas. The separation of the modern species is likely the result of climate change which displaced Pinicola habitat to subarctic northern and subalpine Himalayan regions. Possibly, the ancestors of the North American Pine Grosbeaks were wind-blown individuals which arrived via the northern Pacific, as the Bering Land Bridge was generally submerged in the Late Miocene.(Wikipedia)

Adults have a long forked black tail, black wings with white wing bars and a large bill. Adult males have a rose-red head, back and rump. Adult females are olive-yellow on the head and rump and grey on the back and underparts. Young birds have a less contrasting plumage overall, appearing shaggy when they moult their colored head plumage.

Its voice is geographically variable, and includes a whistled pui pui pui or chii-vli. The song is a short musical warble.

The breeding habitat of the Pine Grosbeak is coniferous forests. They nest on a horizontal branch or in a fork of a conifer. This bird is a permanent resident through most of its range; in the extreme north or when food sources are scarce, they may migrate further south.

The Pine Grosbeak forages in trees and bushes. It mainly eats seeds, buds, berries and insects. Outside of the nesting season, it often feeds in flocks.

The Pine Grosbeak, together with its Himalayan relative the Crimson-browed Finch (P. subhimachala), represents an ancient divergence from the same stock that also gave rise to the true bullfinches (Pyrrhula). The Pinicola lineage diverged from its relatives perhaps a dozen million years ago, during the Clarendonian faunal stage of the mid-Miocene.

At the same time, the evolutionary radiation of Pyrrhula throughout Eurasia and the Holarctic expansion of the closely related Leucosticte mountain finches and relatives began. These genera evolved in the interior of Asia, and thus the original Pinicola stock was probably already a conifer forest bird living to the north of the Himalayas. The separation of the modern species is likely the result of climate change which displaced Pinicola habitat to subarctic northern and subalpine Himalayan regions. Possibly, the ancestors of the North American Pine Grosbeaks were wind-blown individuals which arrived via the northern Pacific, as the Bering Land Bridge was generally submerged in the Late Miocene.(Wikipedia)

Ovenbird

Case 2, Bird 12: The Ovenbird

The Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) is a small songbird of the New World warbler family (Parulidae). This migratory bird breeds in eastern North America and winters in Central America, many Caribbean Islands, Florida, and northern Venezuela.

Their breeding habitats are mature deciduous and mixed forests, especially sites with little undergrowth, across Canada and the eastern United States. For foraging, it prefers woodland with abundant undergrowth of shrubs; essentially, it thrives best in a mix of primary and secondary forest. Ovenbirds migrate to the southeastern United States, the Caribbean, and from Mexico to northern South America. The birds are territorial all year round, occurring either singly or (in the breeding season) as mated pairs, for a short time accompanied by their young. During migration, they tend to travel in larger groups however, dispersing again once they reach their destination.

In winter, they dwell mainly in lowlands, but may ascend up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) ASL e.g. in Costa Rica. The first migrants leave in late August and appear on the wintering grounds as early as September, with successive waves arriving until late October or so. They depart again to breed between late March and early May, arriving on the breeding grounds throughout April and May. Migration times do not seem to have changed much over the course of the 20th century.

This bird seems just capable of crossing the Atlantic, as there have been a handful of records in Norway, Ireland and Great Britain. However, half of the six finds were of dead birds. A live Ovenbird on St Mary’s, Isles of Scilly in October 2004 was in bad condition, but died despite being taken into care.

Ovenbirds forage on the ground in dead leaves, sometimes hovering or catching insects in flight. This bird frequently tilts its tail up and bobs its head while walking; at rest, the tail may be flicked up and slowly lowered again, and alarmed birds flick the tail frequently from a half-raised position. These birds mainly eat terrestrial arthropods and snails, and also include fruit in their diet during winter.

The nest, referred to as the “oven” (which gives the bird its name), is a domed structure placed on the ground, woven from vegetation, and containing a side entrance. Both parents feed the young birds. The placement of the nest on the ground makes predation by chipmunks (Tamias) a greater concern than for tree-nesting birds. Chipmunks have been known to burrow directly into the nest to eat the young birds.

The Ovenbird is vulnerable to nest parasitism by the Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater), which is becoming more plentiful in some areas. However, the Ovenbirds’ numbers appear to be remaining stable. Altogether, it is not considered a threatened species by the IUCN.(Wikipedia)

Their breeding habitats are mature deciduous and mixed forests, especially sites with little undergrowth, across Canada and the eastern United States. For foraging, it prefers woodland with abundant undergrowth of shrubs; essentially, it thrives best in a mix of primary and secondary forest. Ovenbirds migrate to the southeastern United States, the Caribbean, and from Mexico to northern South America. The birds are territorial all year round, occurring either singly or (in the breeding season) as mated pairs, for a short time accompanied by their young. During migration, they tend to travel in larger groups however, dispersing again once they reach their destination.

In winter, they dwell mainly in lowlands, but may ascend up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) ASL e.g. in Costa Rica. The first migrants leave in late August and appear on the wintering grounds as early as September, with successive waves arriving until late October or so. They depart again to breed between late March and early May, arriving on the breeding grounds throughout April and May. Migration times do not seem to have changed much over the course of the 20th century.

This bird seems just capable of crossing the Atlantic, as there have been a handful of records in Norway, Ireland and Great Britain. However, half of the six finds were of dead birds. A live Ovenbird on St Mary’s, Isles of Scilly in October 2004 was in bad condition, but died despite being taken into care.

Ovenbirds forage on the ground in dead leaves, sometimes hovering or catching insects in flight. This bird frequently tilts its tail up and bobs its head while walking; at rest, the tail may be flicked up and slowly lowered again, and alarmed birds flick the tail frequently from a half-raised position. These birds mainly eat terrestrial arthropods and snails, and also include fruit in their diet during winter.

The nest, referred to as the “oven” (which gives the bird its name), is a domed structure placed on the ground, woven from vegetation, and containing a side entrance. Both parents feed the young birds. The placement of the nest on the ground makes predation by chipmunks (Tamias) a greater concern than for tree-nesting birds. Chipmunks have been known to burrow directly into the nest to eat the young birds.

The Ovenbird is vulnerable to nest parasitism by the Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater), which is becoming more plentiful in some areas. However, the Ovenbirds’ numbers appear to be remaining stable. Altogether, it is not considered a threatened species by the IUCN.(Wikipedia)

Red-crowned Woodpecker

Case 2, Bird 13: The Red-crowned Woodpecker

The Red-crowned Woodpecker, Melanerpes rubricapillus, is a resident breeding bird from southwestern Costa Rica south to Colombia, Venezuela, the Guianas and Tobago.

This woodpecker occurs in forests and semi-open woodland and cultivation. It nests in a hole in a dead tree or large cactus. The clutch is two eggs, incubated by both sexes, which fledge after 31–33 days.

Adults are 20.5 cm long and weigh 48g. They have a zebra-barred black and white back and wings and a white rump. The tail is black with some white barring, and the underparts are pale buff-brown.

The male has a red crown patch and nape. The female has a buff crown and duller nape. Immature birds are duller, particularly in the red areas of the head and neck. M. r. terricolor of Tobago is larger and darker-breasted than the nominate race.

Red-crowned Woodpeckers feed on insects, but will take fruit and visit nectar feeders.

This common and conspicuous species gives a rattling krrrrrl call and both sexes drum on territory.(Wikipedia)

This woodpecker occurs in forests and semi-open woodland and cultivation. It nests in a hole in a dead tree or large cactus. The clutch is two eggs, incubated by both sexes, which fledge after 31–33 days.

Adults are 20.5 cm long and weigh 48g. They have a zebra-barred black and white back and wings and a white rump. The tail is black with some white barring, and the underparts are pale buff-brown.

The male has a red crown patch and nape. The female has a buff crown and duller nape. Immature birds are duller, particularly in the red areas of the head and neck. M. r. terricolor of Tobago is larger and darker-breasted than the nominate race.

Red-crowned Woodpeckers feed on insects, but will take fruit and visit nectar feeders.

This common and conspicuous species gives a rattling krrrrrl call and both sexes drum on territory.(Wikipedia)

Snow Bunting

Case 2, Bird 14: The Snow Bunting

The Snow Bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis), sometimes colloquially called a snowflake, is a passerine bird in the longspur family Calcariidae. It is an arctic specialist, with a circumpolar Arctic breeding range throughout the northern hemisphere. There are small isolated populations on a few high mountain tops south of the Arctic region, including the Cairngorms in central Scotland and the Saint Elias Mountains on the southern Alaska-Yukon border, and also Cape Breton Highlands.

It is fairly large and long-winged for a bunting, 15–18 cm long and with a wingspan of 32–38 cm, and weighing 26–50 g. In flight, it is easily identified by its large white wing patches. The breeding male is unmistakable, with all white plumage and a black back; the breeding female is grey-black where the male is solid black. In winter plumage, both sexes are mottled pale ginger, blackish and white above, and pale ginger and white below, with the males having more white than the females. The bill is yellow with a black tip, all black in summer males. Unlike most passerines, it has feathered tarsi, an adaptation to its harsh environment. No other passerine can winter as far north as this species apart from the Common Raven.

The call is a distinctive rippling whistle, “per,r,r,rit” and the typical Plectrophenax warble “hudidi feet feet feew hudidi”.

It builds its bulky nest in rock crevices. The eggs are blue-green, spotted brown, and hatch in 12–13 days, and the young are already ready to fly after a further 12–14 days.

There are four subspecies, which differ slightly in the plumage pattern of breeding males:

It is very closely related to the Beringian McKay’s Bunting, which differs in having even more white in the plumage. Hybrids between the two occur in Alaska, and they have been considered conspecific by some authors, though they are generally treated as separate species.

The species is not endangered at present, with good populations. It shows little fear of humans, and often nests around buildings in Arctic areas, readily feeding on grain or other scraps put out for it.

The breeding habitat is on tundra, treeless moors, and bare mountains. It is migratory, wintering a short distance further south in open habitats in northern temperate areas, typically on either sandy coasts, steppes, prairies, or low mountains, more rarely on farmland stubble. In winter, it forms mobile flocks. During the last ice age, the Snow Bunting was widespread throughout continental Europe. (Wikipedia)

It is fairly large and long-winged for a bunting, 15–18 cm long and with a wingspan of 32–38 cm, and weighing 26–50 g. In flight, it is easily identified by its large white wing patches. The breeding male is unmistakable, with all white plumage and a black back; the breeding female is grey-black where the male is solid black. In winter plumage, both sexes are mottled pale ginger, blackish and white above, and pale ginger and white below, with the males having more white than the females. The bill is yellow with a black tip, all black in summer males. Unlike most passerines, it has feathered tarsi, an adaptation to its harsh environment. No other passerine can winter as far north as this species apart from the Common Raven.

The call is a distinctive rippling whistle, “per,r,r,rit” and the typical Plectrophenax warble “hudidi feet feet feew hudidi”.

It builds its bulky nest in rock crevices. The eggs are blue-green, spotted brown, and hatch in 12–13 days, and the young are already ready to fly after a further 12–14 days.

There are four subspecies, which differ slightly in the plumage pattern of breeding males:

- Plectrophenax nivalis nivalis. Arctic Europe, Arctic North America. Head white, rump mostly black with a small area of white.

- Plectrophenax nivalis insulae. Iceland, Faroe Islands, Scotland. Head white with a blackish collar, rump black.

- Plectrophenax nivalis vlasowae. Arctic Asia. Head white, rump mostly white.

- Plectrophenax nivalis townsendi. Aleutian Islands, Kamchatka, coastal far eastern Siberia. As vlasowae, but slightly larger.

It is very closely related to the Beringian McKay’s Bunting, which differs in having even more white in the plumage. Hybrids between the two occur in Alaska, and they have been considered conspecific by some authors, though they are generally treated as separate species.

The species is not endangered at present, with good populations. It shows little fear of humans, and often nests around buildings in Arctic areas, readily feeding on grain or other scraps put out for it.

The breeding habitat is on tundra, treeless moors, and bare mountains. It is migratory, wintering a short distance further south in open habitats in northern temperate areas, typically on either sandy coasts, steppes, prairies, or low mountains, more rarely on farmland stubble. In winter, it forms mobile flocks. During the last ice age, the Snow Bunting was widespread throughout continental Europe. (Wikipedia)

White-breasted Nuthatch

Case 2, Bird 15: The White-breasted Nuthatch

The White-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) is a small songbird of the nuthatch family which breeds in old-growth woodland across much of temperate North America. It is a stocky bird, with a large head, short tail, powerful bill and strong feet. The upperparts are pale blue-gray, and the face and underparts are white. It has a black cap and a chestnut lower belly. The nine subspecies differ mainly in the color of the body plumage.

Like other nuthatches, the White-breasted Nuthatch forages for insects on trunks and branches, and is able to move head-first down trees. Seeds form a substantial part of its winter diet, as do acorns and hickory nuts that were stored by the bird in the fall. The nest is in a hole in a tree, and the breeding pair may smear insects around the entrance as a deterrent to squirrels. Adults and young may be killed by hawks, owls and snakes, and forest clearance may lead to local habitat loss, but this is a common species with no major conservation concerns over most of its range.

Like other members of its genus, the White-breasted Nuthatch has a large head, short tail, short wings, a powerful bill and strong feet; it is 13–14 cm (5–6 in) long, with a wingspan of 20–27 cm (8–11 in) and a weight of 18–30 g (0.64–1.06 oz).

The adult male of the nominate subspecies, S. c. carolinensis, has pale blue-gray upperparts, a glossy black cap (crown of the head), and a black band on the upper back. The wing coverts and flight feathers are very dark gray with paler fringes, and the closed wing is pale gray and black, with a thin white wing bar. The face and the underparts are white. The outer tail feathers are black with broad diagonal white bands across the outer three feathers, a feature readily visible in flight.

The female has, on average, a narrower black back band, slightly duller upperparts and buffer underparts than the male. Her cap may be gray, but many females have black caps, and cannot be reliably distinguished from the male in the field. In the northeastern United States, at least 10% of females have black caps, but the proportion rises to 40–80% in the Rocky Mountains, Mexico and the southeastern U.S. Juveniles are similar to the adult, but duller plumaged.

Like other nuthatches, this is a noisy species with a range of vocalizations. The male’s mating song is a rapid nasal qui-qui-qui-qui-qui-qui-qui. The contact call between members of a pair, given most frequently in the fall and winter is a thin squeaky nit, uttered up to 30 times a minute. A more distinctive sound is a shrill kri repeated rapidly with mounting anxiety or excitement kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri; the Rocky Mountains and Great Basin subspecies have a higher, faster yididitititit call, and Pacific birds a more nasal beeerf.

Three other, significantly smaller, nuthatches have ranges which overlap that of White-breasted, but none has white plumage completely surrounding the eye. Further distinctions are that the Red-breasted Nuthatch has a black eye line and reddish underparts, and the Brown-headed and Pygmy Nuthatches each have a brown cap, and a white patch on the nape of the neck.

The White-breasted Nuthatch has nine subspecies, although the differences are small and change gradually across the range. The subspecies are sometimes treated as three groups based on close similarities in morphology, habitat usage, and vocalizations. These groups cover eastern North America, the Great Basin and central Mexico, and the Pacific coastal regions. The subspecies of the western interior have the darkest upperparts, and eastern S. c. carolinensis has the palest back. The eastern form also has a thicker bill and broader dark cap stripe than the interior and Pacific races. The calls of the three groups differ, as described above. The Great Basin and Eastern forms have been observed in secondary contact on the Great Plains, where they do not seem to mix. (Wikipedia)

Like other nuthatches, the White-breasted Nuthatch forages for insects on trunks and branches, and is able to move head-first down trees. Seeds form a substantial part of its winter diet, as do acorns and hickory nuts that were stored by the bird in the fall. The nest is in a hole in a tree, and the breeding pair may smear insects around the entrance as a deterrent to squirrels. Adults and young may be killed by hawks, owls and snakes, and forest clearance may lead to local habitat loss, but this is a common species with no major conservation concerns over most of its range.

Like other members of its genus, the White-breasted Nuthatch has a large head, short tail, short wings, a powerful bill and strong feet; it is 13–14 cm (5–6 in) long, with a wingspan of 20–27 cm (8–11 in) and a weight of 18–30 g (0.64–1.06 oz).

The adult male of the nominate subspecies, S. c. carolinensis, has pale blue-gray upperparts, a glossy black cap (crown of the head), and a black band on the upper back. The wing coverts and flight feathers are very dark gray with paler fringes, and the closed wing is pale gray and black, with a thin white wing bar. The face and the underparts are white. The outer tail feathers are black with broad diagonal white bands across the outer three feathers, a feature readily visible in flight.

The female has, on average, a narrower black back band, slightly duller upperparts and buffer underparts than the male. Her cap may be gray, but many females have black caps, and cannot be reliably distinguished from the male in the field. In the northeastern United States, at least 10% of females have black caps, but the proportion rises to 40–80% in the Rocky Mountains, Mexico and the southeastern U.S. Juveniles are similar to the adult, but duller plumaged.

Like other nuthatches, this is a noisy species with a range of vocalizations. The male’s mating song is a rapid nasal qui-qui-qui-qui-qui-qui-qui. The contact call between members of a pair, given most frequently in the fall and winter is a thin squeaky nit, uttered up to 30 times a minute. A more distinctive sound is a shrill kri repeated rapidly with mounting anxiety or excitement kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri; the Rocky Mountains and Great Basin subspecies have a higher, faster yididitititit call, and Pacific birds a more nasal beeerf.

Three other, significantly smaller, nuthatches have ranges which overlap that of White-breasted, but none has white plumage completely surrounding the eye. Further distinctions are that the Red-breasted Nuthatch has a black eye line and reddish underparts, and the Brown-headed and Pygmy Nuthatches each have a brown cap, and a white patch on the nape of the neck.

The White-breasted Nuthatch has nine subspecies, although the differences are small and change gradually across the range. The subspecies are sometimes treated as three groups based on close similarities in morphology, habitat usage, and vocalizations. These groups cover eastern North America, the Great Basin and central Mexico, and the Pacific coastal regions. The subspecies of the western interior have the darkest upperparts, and eastern S. c. carolinensis has the palest back. The eastern form also has a thicker bill and broader dark cap stripe than the interior and Pacific races. The calls of the three groups differ, as described above. The Great Basin and Eastern forms have been observed in secondary contact on the Great Plains, where they do not seem to mix. (Wikipedia)

Rufous-tailed Jacamar

Case 2, Bird 16: The Rufous-tailed Jacamar

The Rufous-tailed Jacamar, Galbula ruficauda, is a near-passerine bird which breeds in the tropical New World in southern Mexico, Central America and South America as far south as southern Brazil and Ecuador.

The jacamars are elegant brightly coloured birds with long bills and tails. The Rufous-tailed Jacamar is typically 25 centimetres (10 in) long with a 5 centimeters (2 in) long black bill. The subspecies G. r. brevirostris has, as its name implies, a shorter bill. This bird is metallic green above, and the underparts are mainly orange, including the undertail, but there is a green breast band. Sexes differ in that the male has a white throat, and the female a buff throat; she also tends to have paler underparts. The race G. r. pallens has a copper-coloured back in both sexes.

This species is a resident breeder in a range of dry or moist woodlands and scrub. The two to four rufous-spotted white eggs are laid in a burrow in a bank or termite mound.

This insectivore hunts from a perch, sitting with its bill tilted up, then flying out to catch flying insects. The bird distinguishes between edible and unpalatable butterflies mainly according to body shape (Chai 1996).

The Rufous-tailed Jacamar’s call is a sharp pee-op, and the song a high thin peeo-pee-peeo-pee-pe-pe, ending in a trill.(Wikipedia)

The jacamars are elegant brightly coloured birds with long bills and tails. The Rufous-tailed Jacamar is typically 25 centimetres (10 in) long with a 5 centimeters (2 in) long black bill. The subspecies G. r. brevirostris has, as its name implies, a shorter bill. This bird is metallic green above, and the underparts are mainly orange, including the undertail, but there is a green breast band. Sexes differ in that the male has a white throat, and the female a buff throat; she also tends to have paler underparts. The race G. r. pallens has a copper-coloured back in both sexes.

This species is a resident breeder in a range of dry or moist woodlands and scrub. The two to four rufous-spotted white eggs are laid in a burrow in a bank or termite mound.

This insectivore hunts from a perch, sitting with its bill tilted up, then flying out to catch flying insects. The bird distinguishes between edible and unpalatable butterflies mainly according to body shape (Chai 1996).

The Rufous-tailed Jacamar’s call is a sharp pee-op, and the song a high thin peeo-pee-peeo-pee-pe-pe, ending in a trill.(Wikipedia)

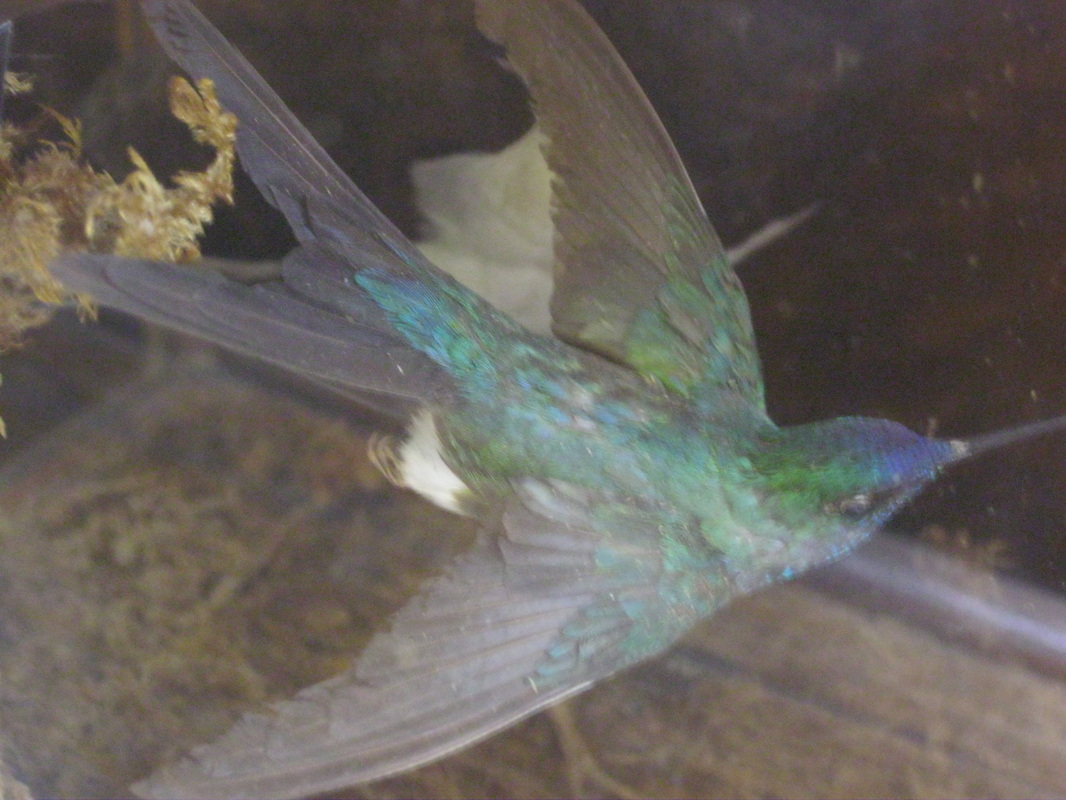

Unidentified Birds

We are looking for the species of Hummingbird if you think you know what that it is please go to our Unidentified Birds page and tell us.